Don’t Use Remdesivir.

Just one month after the US Food and Drug Administration approved remdesivir as an antiviral for the treatment of patients with COVID-19, the WHO yesterday recommended that it not be used, on the basis that it is ineffective and there is “no evidence” it reduces mortality.

Last month, we analysed remdesivir’s use since early January 2020 as a COVD-19 treatment on compassionate grounds. It was used to treat those with severe COVID-19 symptoms, who had both developed pneumonia and required oxygen support. You can read this analysis in full here and we concluded;

“It is an effective therapeutic treatment only for those in a very specific group…for everyone else, not only is remdesivir ineffective but with a 60% chance of adverse side effects and 23% chance of serious adverse side effects, the benefit appears not to outweigh the risk.”

It appears we were right and somewhat ahead of the game.

Remdesivir was the first of the ‘wonder drugs’ peddled as a potential vaccine (despite it being an antiviral not a general vaccine, let alone a pandemic vaccine) that was going to be the saviour for us all and has since been joined by Pfizer/BioNTech’s BNT126b2 and Moderna’s mRNA-1273.*

* Both of these are RNA/mRNA experimental vaccines, a class of vaccine not currently approved for use on any illness anywhere in the world.

There is a vast difference between the compassionate use of any drug as a last resort where the patient may well die regardless, even if that drug contributes to the death of 17% of those to whom it is given [Antinori et al, 2020] and the widespread use of a drug either as a therapeutic or prophylactic.

Ineffective At Best, If Not More Danergous.

The WHO’s Guideline Development Group commented that “remdesivir has no meaningful effect on mortality or on other important outcomes for patients, such as the need for mechanical ventilation or time to clinical improvement.”

This concurs with our earlier conclusion although we went further in highlighting that a 60% rate of adverse side effects and a 23% rate of serious adverse side effects meant remdesivir was not just ineffective but also potentially more dangerous than normal medical care.

Don’t forget that remdesivir has form, having been discontinued as a potential therapeutic treatment for Ebola back in 2014. It is worth noting that during that assessment, the findings were based upon the FDA’s Animal Rule which permits the findings of animal trials to be read-across to efficacy on humans, principally where the risk of human trials is too great. Given Ebola’s mortality rate – although not its R0 (read our previous article to understand why the R0 does not measure severity and is largely irrelevant) – there was nothing wrong with trying but it didn’t work.

Again, nothing wrong for trying this time around on SARS-CoV-2 but it doesn’t work for the vast majority of people. It provides some therapeutic benefit for that very narrow group but even then its principal benefit is reducing the level of oxygen support required, e.g. mechanical ventilation to ECMO or low-flow oxygen administration to normal oxygen saturation.

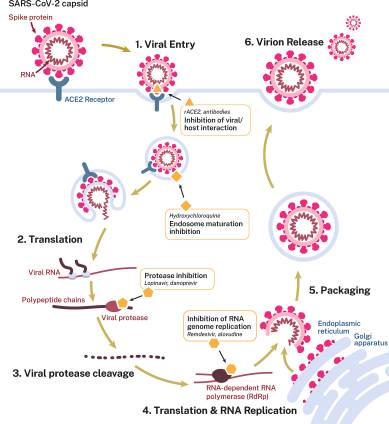

Intracellular Activation Late In The Replication Cycle.

Another factor that limits remdesivir’s efficacy is its vector-based multi-stage bioactivation. The active metabolite – triphosphate GS-443902 – has to be delivered intracellularly to infected cells where it inhibits SARS-CoV-2’s RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp) – or RNA replicase – which is the catalyst for replication of its viral RNA. The issue is that replication by its very definition occurs after a virion has bound to a host cell; gained intracellular fusion, used tRNA to decode its genome; sent mRNA to the ribosome; formed the two polyprotein chains pp1a & pp1ab and cleaved these into the 16 nonstructural proteins and 4 structural proteins. At that point, the infected cell contains the necessary parts to assemble a new virion with the process being governed by RdRp, with the exoribonuclease (nsp14-ExoN) ensuring that the transcription process is accurate. In an attempt to avoid nsp14-ExoN remdesivir doesn’t aim to stop the RdRp (stopping replication through an immediate ‘chain termination’) but rather disrupt the RdRp (degrading replication through a delayed ‘chain termination’). In simple terms, it throws a spanner into the replication machinery.

SARS-CoV-2’s replication cycle [Eastman et al, 2020].

The risk is that you are targetting a late stage in the replication process, after the virion has infected a host cell and – importantly – ACE2 function has already been affected as a result of ACE2 receptor being the spike glycoprotein’s RBD. We have explained previously the importance both of the ACE2→ angiotensin1-7→ Mas receptor axis and its counterfunction ACE→ angiotensin II→ AT1 receptor axis. Targetting RdRp interruption is after these axes have been affected, which is why remdesivir can’t be considered as a vaccine (because it isn’t one) and shouldn’t be considered as antiviral as the damage has already been done by the time the RNA replicase is looking to assemble new virions.

If one were researching a vaccine, our money would be on targetting the interraction between nsp10 and nsp14-ExoN, where nsp10 effectively shields the effective function of nsp14-ExoN as a result of their related positioning.

It is perhaps unsurprising (although not to us) that the more you evaluate remdesivir, the more you realise it isn’t an effective antiviral treatment for COVID-19. Appositely timed to pick up on WHO’s recommendation, the British Medical Journal today carries a very well-written article. It can be read in full here but it comments:

“None of the randomised controlled trials published so far, however, have shown that remdesivir saves significantly more lives than standard medical care”…”the World Health Organization’s Solidarity trial has published interim results showing that the drug has no significant impact on mortality, length of hospital stay, or need for ventilation among hospitalised patients.”

“This represents some of the strongest evidence yet that remdesivir is unlikely to be the lifesaving drug for the masses that many have hoped for.”

Groundhog Day Not A Great Humanity Day.

The BMJ article author, Jeremy Hsu, asks the very incisive question of whether remdesivir ‘is just Tamiflu redux?’.

Tamiflu is the brand name of oseltamivir, one of the two main antivirals given in the UK as the seasonal or winter flu jab. We have previously analysed the efficacy of both oseltamivir and zanamivir and highlighted that they are largely ineffective – as with remdesivir – and can cause adverse and serious adverse side effects – as with remdesivir.

There are currently more than 320 potential vaccines in development for COVID-19 [Le TT et al, 2020] and every time a drugs company has a ‘positive’ announcement, the euphoria, hysteria and general bullshit kicks in. ‘Oh, we can’t survive without a vaccine’, ‘life can’t go back to normal until a vaccine makes big pharma lots of money is rushed out’. With such a wide universe of candidates, statistically one or more therapeutic or prophylactic treatments will be viable in due course, although ‘in due course’ means after it has been comprehensively tested and shown on an evidence-based basis to be effective and safe. Not ‘inconclusive’ or ‘no clear benefit’ or ‘modest benefit at best’ or ‘no different to standard medical care’ or ‘unclear if better than existing, common medications’.

No Vaccine Required And Certainty Not An Experimental One.

Our view is unchanged. A vaccine is not required because the 99% of people who get SARS-CoV-2 don’t need one – as they overcome the infection via their innate immune system only without requiring immunologial memory – and the frail don’t have immunological memory so one won’t work on them.

Given the experimental nature of RNA/mRNA vaccines, we would go further and predicate that the higher risks of autoimmunity and immunopathology, especially in those with compromised immune systems who are natrually going to be in high risk groups, make this type of vaccine rather dangerous. Playing with experimental vaccines, taking shortcuts through accelerated regulatory approval (aka ‘don’t undertake the usual trials’ and ‘mice and macaques are identical to humans’) and ignoring standard procedures for something intended to be a pandemic vaccine is reckless in the extreme.

And for the ‘killer virus of death’ that continues to not kill people, especially those it infects, as it becomes more like CoV-OC43 – very transmissible but less virulent, attenuating naturally – an experimental vaccine is almost absurd.

As we have been very specific about previously:

“An antiviral may well be the better route to explore when compared with experimental RNA/mRNA vaccine. Perhaps the best outcome that can be hoped for is an antiviral that is 50% effective for those in high risk groups, where it can provide them with passive immunity.”

“This would benefit those with weakened immune systems and lacking immunological memory, with an antiviral in effect giving them a second line of defence.”

As for the first line of defence, the body’s immune system is more than up to the task. The pattern recognition receptors of the innate immune system recognise the pathogen-associated molecular patterns of coronanvirus RNA. The increased pathogen-specific antibody generation in older people, with some 60-85 year olds generating more than 3x the levels of antigen-specific antibodies than 15-39 year olds [Fan et al, 2020], suggests activation of memory lymphocytes from one or more previous infections, whether from other orthocoronavirinae or other viruses.

CD8+ T Cells.

Of particular interest is the existence of above average levels of memory CD8+ T cells in individuals who have had SARS-CoV-2 and developed COVID-19 symptoms as well as those who have not. CD8+ are the main cytotoxic adaptive immune response, targeting infected host cells. Previous research after SARS-CoV in 2002 showed memory CD8+ T cells remained in the system for years after primary infection, which is the very concept of immunological memory.

This highlights further a crucial point we first raised in September, in that designating SARS-CoV-2 as ‘new’ in early 2020 was incorrect & misleading because everyone was made to think it didn’t exist prior to that time and no earlier event in time had any relevance. It should have been designated ‘newly-discovered’ as there is a wide body of evidence that shows it has been around for a while, evolving through recombination, and the majority of individuals may well have had it prior to this year. This would explain the presence of memory T cells in those who have not had SARS-CoV-2 this year.

CD8+ T cells may be as or even more important than B cells in the focus of any vaccine or antiviral for high risk groups, especially if it aims to provide passive immunity to those with compromised immune systems or lacking immunological memory.